On trusting the veracity of source material

Or, if it's published in a book, it must be true?

Inland Empire locals know about Martin Sanchez’s Tio’s Tacos—a monument to the artistic potential of recycled materials, very much in the spirit of Los Angeles’ Watts Towers, except you can eat tacos there. Like Sabato “Simon” Rodia’s Watts Towers, it is made up of fragments of found objects from the artist’s community.

While I’ve known about Tio’s Tacos for as long as I’ve lived in Riverside, I didn’t learn about Watts Towers until I began to write this book about my grandfathers Rufus and Brad Keeler, despite being a Southern California native who grew up in its backyard. The only reason it is even on my radar, having now lived in the I.E. twice as long as I had lived in L.A., is because of its connection to Malibu Potteries.

But it turns out that the only “real” connection between Watts Towers and Malibu Potteries is tenuous at best—or seems to be, as far as I can tell.

There’s that old joke that if you read it on the internet, it must be true. The same goes for if you read it in a newspaper or a book or in an archive. What is a researcher to do if you can’t trust your source material?

Of Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers, The Guardian writes, “Using nothing but found objects, he was the ultimate recycler. His decorations are broken bottles, mostly 7-Up and Canada Dry green; old crockery collected for him by local children (when they weren't vandalising his work) and tiles. Many tiles came from the Malibu tile company where Rodia worked for 10 years.” (Emphasis my own.) Yet the comprehensive listing of Malibu Potteries employees has no Rodia on its roster (nor Rodilla, as it alternately spelled), and Bud Goldstone who wrote the comprehensive and definitive book on Watts Towers continually refutes the statement that Rodia worked for Malibu.

But the plot—or the mortar? the grout?—thickens.

An informal interview I did with Brian Kaiser, who currently owns our Keeler family home in South Gate which itself is a monument to the versatility and durability of tile, and who has been studying my great-grandfather’s work for as long as he has owned the house (since the 80s) says that while Rodia did not work for Malibu, he did work for Rufus at CalCo, the pottery that Rufus founded before he went on to work for Malibu. Further, he worked for Taylor Tilery and American Encaustic. However, there’s no source online where I—or others— can confirm these things, and so the mis-information keeps being referenced. Sure, that Guardian article is from 2011, but enough people have read it that the myth of Rodia with his pockets stuffed with broken Malibu tile keeps being perpetuated, including by the Adamson House itself—the National Historic Site and California Historical Landmark-designated treasures of Malibu tile and home to the Malibu Lagoon Museum. Further, it was included in a book about the origins of the City of Malibu and Pacific Coast Highway, The King and Queen of Malibu, by David K. Randall and published by W.W. Norton.

How to know who (which source) to trust?

I don’t. I am simply following the trail, and laying out the possibilities. Could Rodia have worked for Malibu in some capacity? Sure. Could he have worked for some other tilery that made tiles using Malibu designs? That, too, is a possibility.

But I’m not actually here to talk about Watts Towers.

*

On the Adamson House site, in the archives, are numerous photographs from the Malibu Potteries heyday. There are two which purport to be of Malibu employees with “the Keeler boys.” But guess what? They’re not.

One photo shows Lillian Ball, Rufus’s assistant and neighbor on Victoria Ave in South Gate, with two young boys it identifies as Bradley and Phillip Keeler. For readers who are unfamiliar with my story, my mother is the youngest of three children and the only daughter of Bradley Keeler. Bradley was the oldest of the four children born to Rufus and Mary Keeler, Rufus being the plant manager and “tile genius” behind the success of Malibu Potteries.

Malibu was in operation from 1926 to 1931.

Rufus’s four children were born in 1913 (Brad), 1920 (Jean, the only daughter), 1925 (Byron, aka Bud) and 1928 (Phillip).

See the problem?

In 1926, when the factory opened, Brad would have already been 13 years old. The child in the photo is maybe (?) 9 years old. The younger child, definitely a boy, looks to be about 4 years old. The second boy, Bud, in the Keeler family would have only been 1 year old in 1926. Phillip would not be born for two more years.

Or lets take it from the other direction:

In 1931, when the factory closed, Brad would have been 18 years old. Jean would have 11. Bud would have been 6. Could the older child be Bud? It’s possible, if I’ve completely mis-gauged his age. The younger? Phil would have been only 3 years old.

Is it plausible that these boys are Bud and Phil?

Let’s take another photo from the same archives, this time of Don and Dorothy Prouty, again with boys identified as Phillip and Bradley. Same date comparison. If it’s 1926, Brad would be 13; Phil would not have been born, and Bud would have been 1. If it’s 1931, Brad would be 18, Bud would be 6, and Phil would be 3.

I look at these photos and wonder, are they even the same set of boys? If they aren’t Keelers, who are they? And suddenly I find myself mired in looking up on Ancestry.com any of the higher-ups at Malibu to see who among them might have kids. Did the Proutys themselves? How about the Balls? Could those simply be their own children?

I really don’t know. But I can tell you, research is a slippery slope. Do I really know who these boys are? I feel like I do because, along with the misinformation about Rodia, it calls into question the veracity of the other details on their site. Who did the initial research and what source material did they rely on? Where is it?

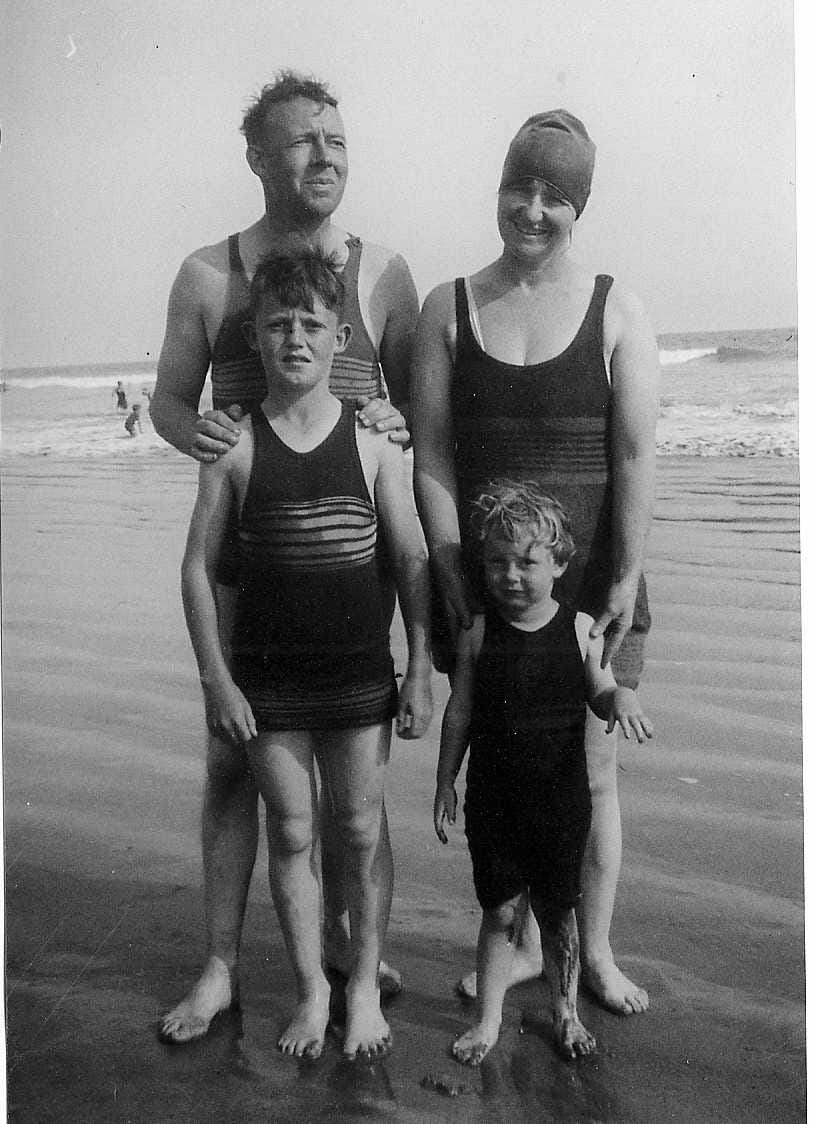

I’ll leave you with this, a family of picture of Rufus, Mary, Brad, and Jeanne on the Malibu beach, circa 1926.

https://www.rizzoliusa.com/book/9780847838493/

If he didn't work for Malibu Pottery he probably gathered from the bottom of the hill behind the Serra Retreat or some secret spots in Topanga where imperfect ones were piled...

I'm sure you are familiar with this, but just in case... The Keeler house even made the back cover.