You Are What You Read

You know how that saying goes. Of course, you’re not literally what you eat, because: cannibalism. But it’s true that what you consume affects everything about you.

For instance, if I choose to eat an entire sleeve of Girl Scout Thin Mints, my blood sugar will go crazy and my head will hurt—my body’s signals that I’ve made a dumb move. Sure, maybe the cookies were worth it in the moment, but my body makes it known that it’s unhappy with my choice.

The same goes for reading. If all I read was the back of the cereal box, then I’d know a lot about its nutritional value, but I’d know nothing about contemporary literature and there’d be very little that would be transferable to other aspects of my life, and probably I’d never be invited to parties and would live a very lonely life, just my cereal and me.

I’m not going to rant about the election today. Instead I want to share that, like most everyone these days, I have friends and family who fall differently along the political spectrum than I do. While we are all readers, my anecdotal observation is that what they read is different from what I read, and that in turn affects our “reality”. What we choose to read can reaffirm our world view, or expand it.

I recently found an interesting old Smithsonian article (2017), which in turn cites a fifty-year-old quote by one of earliest pioneers of the internet to that effect:

"With the diversity of information channels available, there is a growing ease of creating groups having access to distinctly differing models of reality, without overlap… Will members of such groups ever again be able to talk meaningfully to one another? Will they ever obtain at least some information through the same filters so that their images of reality will overlap to some degree?” [emphasis my own]

This article focuses on science, but it got me thinking about what different kinds of novels conservatives and liberals might read. Did you know there’s a Conservative Fiction Books TikTok? There’s also a Conservative Book Society, and a big spreadsheet of the Greatest Conservative Novels of All Time.

It makes me think about what we say about reading and empathy, but it’s not just the reading itself—it’s the choices that we make about what we read. Sure, school requirements are one thing, but the surest way to get a kid not to want to read something is to assign it in the classroom.

The pendulum of my own reading habits over the years has swung wildly. I was an early and active reader, until in 7th grade GATE I had to read The Red Badge of Courage. I just couldn’t get through it, and thus learned how to fake it in a book report. Later, in AP Lit, we were assigned Tess of the D’urbervilles, where I famously got my teacher talking about himself and thus avoided my oral presentation for at least one class period.

But when I was able to choose what to read? That’s what hooked me on reading. Never mind that what I was most interested in involved incest, arsenic, and children cruelly confined to an attic. Or books involving pets coming back from the dead, trees that swallow people, ghosts, and magic. But I suppose the single most telling defining characteristic of those books? Their characters, and their authors, looked a lot like me.

But as I got older, I started to explore a world that was larger than the one I knew. I read The Color Purple. Like Water for Chocolate. Rubyfruit Jungle. Unbearable Lightness of Being. Lolita. I didn’t think about why I wanted to read those books, I just did. And then again my focus shifted when I had kids as I rarely had time to lose myself in a book unless it was one I was reading to them. It took another decade for my personal reading habits to resurface, but by then I was working a lot.

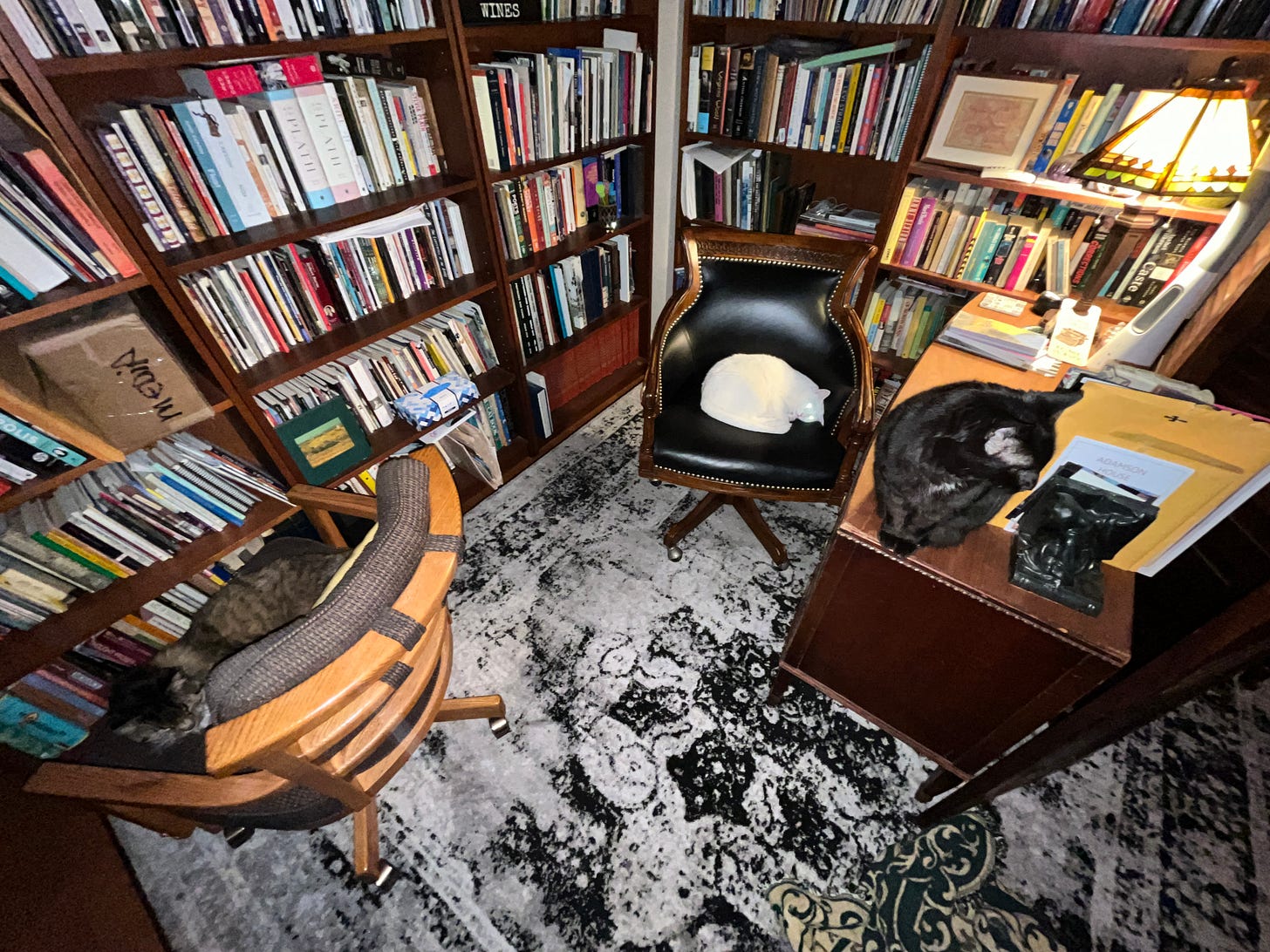

Discovering audiobooks was transformational and allowed me to enjoy books while doing other things. Sure, I’m still old-school in that I love physical books, so much so that I often buy the book and borrow its audio companion from the library. Or, in some cases, books that I’ve purchased or been gifted that I had every intention of reading sit on my TBR pile for years because they are so intimidatingly huge, or I stop and start so many times that I lose my place. In those cases, I have been able to move the books off my TBR pile by listening to them instead. Sure, it’s not exactly the same experience, but if the idea is to get the information into my brain, and therefore into the database that informs my critical thinking, it’s well worth the trade.

This week, I finished The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates and The Library Book by Susan Orlean. I feel changed by both books. Above all, I’m drawn to books that expand my understanding of the world. The Message is one of those books.

An example of one way that book changed the way I look at things: I hosted an event last week, and one of the speakers was a young Indigenous woman wearing a Free Palestine t-shirt. To my old brain, there might have been a perceived incongruity, but I’m beginning to see the parallels between the experiences of oppressed peoples everywhere.

One long essay in The Message is about Coates’ journey into Palestine, the way he is treated as an outsider by the Israelis, and the struggle for Palestinian independence which is very literally under siege as I write this. There are points of reference that I can never access because of my whiteness and my ancestral roots. We move through the world based on the facts of our bodies.

Which brings me to two hefty tomes in my TBR pile: The Warmth of Other Suns and Caste, both by Isabel Wilkerson. I’ve had them literally for several years, and they’ve moved around the house a lot but I have yet to crack open their covers. I knew I wanted to read them, but reading something that literally and figuratively dense is a commitment. Then last week when searching for something to watch on a streaming service, my husband and I watched Origin, the story of how Wilkerson came to write Caste. In it, she dramatizes how she came to the realization that there were parallels in the systemic oppression of India’s “untouchable” caste, Germany’s oppression (and annihilation) of the Jewish people, and the Black American experience through enslavement and all the way into the present.

After we finished the movie and those basic principles were imprinted in my brain, I felt ready to enter Wilkerson’s books, so I checked the Libby app for copies of Warmth and Caste to borrow. I’m now working my way through the latter and just got notified of that my copy of the former is ready to borrow.

I think about all of us, our choice of media sources, and I think about this election.

What kind of person, thinker, voter, might I have been had I stuck with books that only serve to reinforce, not broaden, my world view? I’d like to think that all of us are capable of growth. I’d like to think that those friends and family—fellow readers—might one day decide that they too are ready. That they will pick up that transformative book; that our images of reality may, in time, overlap again.